STIGMA, NEGATIVE ATTITUDES AND DISCRIMINATION TOWARDS MENTAL ILLNESS: STIGMA AS A PREDICTOR OF SERVICE ACCESS, TREATMENT AND SOCIAL INTEGRATION

Abstract

Mental disorders have a high prevalence that is statistics with regards to mental disorders as important increasing, according to WHO mental disorders are causes of disability issued by the main world health among the leading causes of disease worldwide, accounting for around 6.2% of the total disease burden as authority, continues with the definition of stigma and reflecting on the attitude of the general public towards measured in DALYs1. People with mental illness are mental illness and the role of the media as a mediating subject to discrimination which impacts most areas of their lives2 3. These forms of social exclusion occur at home, at work, in personal life, in social activities, in healthcare and in the media4 5. The purpose of this paper is to reflect the impact of Stigma on people with mental illness related to access to psychiatric services, treatment and its consequences for the individual and society. From the literature review we will examine how stigma affected access to services, diagnosis and treatment of people with mental illness as well as the impact of stigma on some aspects of their lives. The article begins by overviewing the factor. It then looks at some of the practical implications of the discrimination and prejudice that arise out of stigma, particularly in respect of use of the health care system and the cost of not seeking help. Finally, an overview is provided on what is known to date about the effectiveness of different approaches that have been adopted or might in future be adopted to effectively tackle stigma.

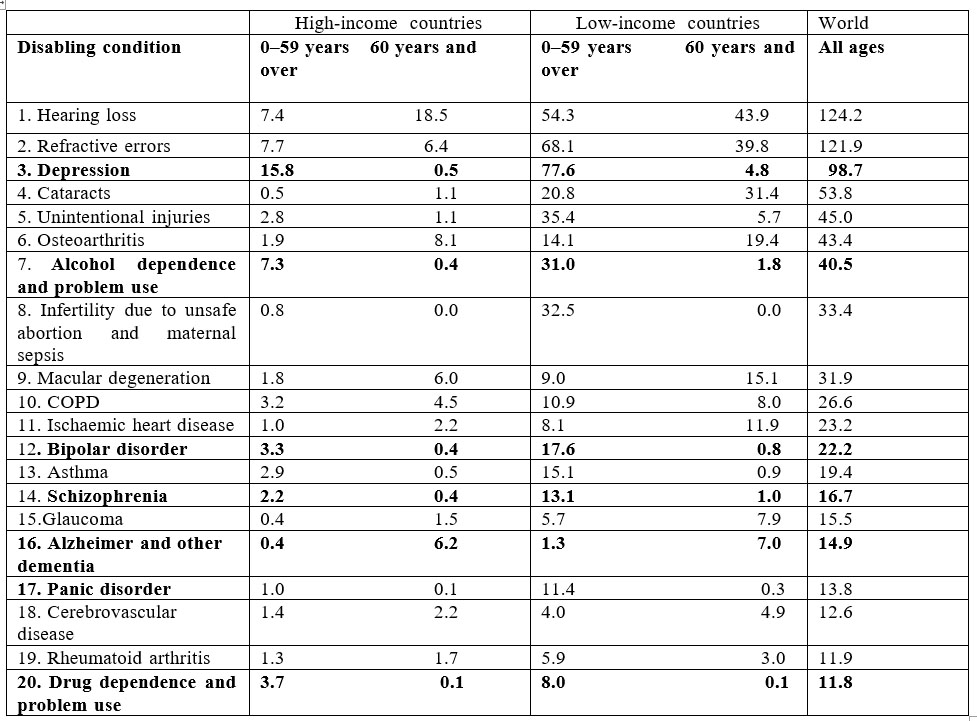

According to the statistics issued by WHO, mental disorders such as depression, psychoses (e.g. bipolar disorder and schizophrenia), alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders, panic disorder, Alzheimer and other dementia are among the 20 leading causes of disability (Table 9). The pattern differs between the high income countries and the low- and middle-income countries6.

In all regions, neuropsychiatric conditions are the most important causes of disability, accounting for around one third of YLD (years lost due to disability) among adults aged 15 years and over, as it can be observed from the table above.

The disabling burden of neuropsychiatric conditions is almost the same for males and females, but the major contributing causes are different. While depression is the leading cause for both males and females, the burden of depression is 50% higher for females than males. Females also have a higher burden from anxiety disorders, migraine and Alzheimer and other dementias. In contrast, the male burden for alcohol and drug use disorders is nearly seven times higher than that for females, and accounts for almost one third of the male neuropsychiatric burden. In both low- and middle-income countries, and high-income countries, alcohol use disorders are among the 10 leading causes of YLD. This includes only the direct burden of alcohol dependence and problem use. The total attributable burden

of disability due to alcohol use is much larger7.

Despite the high prevalence of mental illness, the reality is that only a minority of those who would benefit from treatment for mental illness actually seek it and many of those who succeed to have access to services and get a diagnostic, discontinue treatment prematurely despite the severity of illness and its health, social and economic consequences. Unfortunately, mental health care services are often not available or are under-utilized, particularly in developing countries. In developed countries, the treatment gap (the % age of individuals who need mental health care but do not receive treatment) ranges from 44% to 70%; in developing countries, the treatment gap can be as high as 90%8. Common barriers to mental health care access include limited availability and affordability of mental health care services, insufficient mental health care policies, lack of education about mental illness, and stigma9. For example, only 34% of people with major depression in Finland seek professional help10. Similar results from other countries in Europe and the United States reveal the problem to be global11 12.

Until getting to the point of seeking help, an individual who experiences symptoms of a mental illness goes through a complex process. At first, if the symptoms are not acute, the person tries to understand them and to get an explanation of their origin. The extent to which the person gets to understand the symptoms relates to the level of education of the person, access to information, mental health literacy and/or exposure to people with mental health problems

The next level is to evaluate the severity of the symptoms and their impact on the personal level of functionality, some of them eventually seek for at hand solutions that would give some temporary relief but, as the symptoms aggravate and the level of functionality decreases, the person takes more into consideration the costs and benefits of accessing a specialized mental health service13. One perceived cost to accessing mental health services might be the risk of stigma. It has been suggested that many people hesitate to use mental health services because they do not want to be labeled a “psychiatric patient” and want to avoid the negative consequences connected with stigma14.

But what is stigma? Stigma is a mark of disgrace that sets a person apart. When a person is labelled by their illness they are seen as part of a stereotyped group. Negative attitudes create prejudice which leads to negative actions and discrimination Stigma brings experiences and feelings of shame, blame, hopelessness, distress, misrepresentation in the media and most importantly reluctance to seek and/or accept help15.

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified stigma and discrimination towards mentally ill individuals as “the single most important barrier to overcome in the community”, and the WHO’s Mental Health Global Action Program (mhGAP) cited advocacy against stigma and discrimination as one of its four core

strategies for improving the state of global mental health16 17.Stigma related to mental illness often comes from ignorance. At a time when there is an unprecedented volume of information in the public domain, the level of accurate knowledge about mental illnesses also called sometimes ‘mental health literacy’ is low18. For example, a population survey in England, found that most people (55%) believe that the statement ‘someone who cannot be held responsible for his or her own actions’ describes a person who is mentally ill19. Most of the respondents (63%) thought that fewer than 10% of the population would experience a mental illness at some time in their lives. A 2006 Australian study found that:

·nearly 1 in 4 of people felt depression was a sign of personal weakness and would not employ a person with depression

·around a third would not vote for a politician with depression

·42% thought people with depression were unpredictable

·one in 5 said that if they had depression they would not tell anyone

·nearly 2 in 3 people surveyed thought people with schizophrenia were unpredictable and a quarter felt that they were dangerous20

This ignorance needs to be redressed by conveying more factual knowledge to the general public and also to specific groups such as teenagers, including useful information such as how to recognize the features of mental illness and where to get help 21.

In developing and developed countries, limited knowledge about mental illness can prevent individuals from recognizing mental illness and seeking treatment; poor understanding of mental illness also impairs families’ abilities to provide adequate care for mentally ill relatives22.

Along with ignorance comes as a result the negative attitudes and prejudice. Fear, anxiety and avoidance are common feelings for people who do not have mental illness when reacting to those who have23. The reactions of people to act with prejudice in rejecting a minority group usually involve not just negative thoughts but also emotions such as anxiety, anger, resentment, hostility. It is evident that prejudice strongly predict discrimination. The evidence from scientific enquiry and consultation with service users gives a clear message: discrimination means that it is harder for people with a mental illness to marry, have children, work or have a social life. This social exclusion needs to be actively addressed because this is might be the reason for which a minority of people suffering from mental illness seek professional help for themselves. Stigmatizing attitudes are assumed to be one of the major barriers to help seeking.

Although the reasons for stigmatization are not consistent across communities or cultures, perceived stigma by individuals living with mental illness is reported internationally. For instance, the World Mental Health survey data, which included responses from 16 countries in the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the South Pacific, showed that 22.1% of participants from developing countries and 11.7% of participants from developed countries experienced embarrassment and discrimination due to their mental illness. However, the authors note that these figures likely underestimate the extent of stigma associated with mental illness since they only evaluated data on anxiety and mood disorders24.

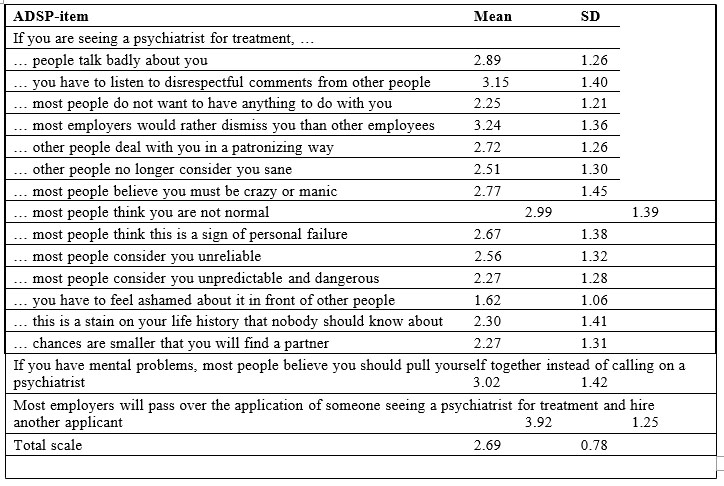

A German study made in 2009 about the stigma of psychiatric treatment and help seeking intentions for depression25 found that with major depression, only 29-52% of those affected seek help during the first year of illness26. Contact to medical services is essential to initiate treatment and reduce the risk of suicide27. In Germany, the median duration of delay until treatment is initiated is 2 years28. Several socio-demographic and illness-related factors have been related to timely help-seeking for depression: women, young people, singles and those severely affected tend to seek help more readily than others29 30 31 32. Within the study, a focus group study with two focus groups comprising 17 patients treated either in a day-clinic or as in-patients, and addressing beliefs about attitudes and reactions of others towards those seeking psychiatric help. In these groups, their real life experiences of stigmatization for seeing a psychiatrist and also their fears and reservations prior to seeing a psychiatrist for the first time were discussed. Additionally, a convenience sample of 29 healthy adults answered a written questionnaire that started with a depression vignette and contained open-ended questions on possible negative consequences when seeing a psychiatrist for this problem and the written questionnaires were content analyzed33. Based on this analysis, a list of 16 items aiming at a comprehensive representation of the ideas voiced in all groups was compiled. Table 2 shows the item wording of the scale generated in this manner. Answers were recorded on a five-point Likert scale anchored with 1 = ”do not agree at all” and 5 = ”agree completely”. Low values thus represent low anticipated discrimination.

Table 2 Item-level statistics for the anticipated discrimination when seeing a psychiatrist (ADSP) scale (n = 2,168–2,295)

The results of this study show that the lowest score was obtained by the statement: ”you have to feel ashamed about it in front of other people” (1,62) and the assumption might be that people do not stigmatize themselves and/or do not share this information so that ”shame feeling” does not appear and correlates with the 4th lowest score (2,30) ”this is a stain on your life history that nobody should know about”.

The second and third lowest scores are: ”most people do not want to have anything to do with you” (2,25) and ”most people consider you unpredictable and dangerous” (2,27) could lead us to the assumption that the perceived discrimination with regards to the fact that a significant number of people would accept to interact with persons diagnosed with depression.

The highest score (3.92) is the statement: ”most employers will pass over the application of someone seeing a psychiatrist for treatment and hire another applicant” shows actually that when it comes to real social and professional integration people diagnosed with mental illness feel that they are profoundly discriminated. It is clear that the anticipated discrimination when seeing the psychiatrist is a very important factor taken into consideration by people who evaluate the possibility of consulting the mental health specialist. There are no studies to tell us how many of the people who need the mental health services do not seek support due to the stigmatization and discrimination. It is obvious that not seeking the needed help leads to poor mental health which has a devastating impact on people s lives and leads to enormous economic costs that have been estimated at

€386 billion (2004 prices) in the EU 25 plus Norway,

Iceland and Switzerland35. The majority of these costs are incurred outside the health care system; the costs of lost productivity from employment can account for as much as 80% of all cost of poor mental health36 . Other impacts include the deterioration of personal relationships and great strain on families37 38 39 a higher-than-average risk of homelessness40 and increased contact with the criminal justice system41. Stigma and prejudice could be one of the main causes of the abuse of human rights that unfortunately continue to be seen in some of the outdated large psychiatric institutions and social care homes that remain the main service that is provided by the mental health systems in some Member States42. This abuse can have many aspects: from denying the basic access to treatment, access to information, access to justice system, especially in the Eastern EU member states, even where community based care dominates, as in much of western Europe, individuals can be just as neglected and isolated within their communities as they were previously in institutions43 .

Despite all statistics and estimations that show an increase of the prevalence of mental disorders and implicitly the huge costs of the lack of treatment we have the situation when stigma can also reduce the willingness of public policymakers to invest in mental health. Some public surveys have indicated that mental health is seen as a low priority when it comes to determining how to allocate health system fund44 45.

To challenge population attitudes about mental disorder should be a continuous process in a world that has a long standing held negative attitude towards people with mental health problems; a series of surveys in England since 1994 indicate that positive attitudes towards mental illness may be decreasing. In 2007 only 78% of individuals disagreed with the statement ‘people with mental illness are a burden on society’ compared with 84% in 2000, while the number of people agreeing with the statement ‘We need to adopt a far more tolerant attitude toward people with mental illness in our society’ was just

84% in 2007 compared with 92% in 199446. A key contributor to the way people with mental disorders are perceive is mass media47. Media tend to place an emphasis on the reporting of rare but sensational tragic events involving people with mental health problems. An analysis of the German tabloid BILD-Zeitung over the first nine months of 1997 found 186 articles related to mental illness, that represents only 0.7% of all news items printed. Thus overall the readers of this newspaper received very little information on mental illness, but 51% of what they did receive was concerned with serious crimes made by people with mental health problems. Inadequate and inflammatory language as well as inaccuracies concerning the judicial process were often used to sensationalize these stories48.

Media might be as well a strong ally over time in creating positive changes in general population attitudes.

In Scotland, where many public campaigns have been continuously developed over time, surveys of public attitudes on mental health have been conducted bi- annually since 2002. The 2006 survey indicated that 85% of participants agreed that ‘people with a mental health problem should have the same rights as anyone else’, 46% agreed that ‘the majority of people with mental health problems recover’ and 40% agreed that ‘people are generally caring and sympathetic to people with mental health problems’. The proportion of people agreeing with the statement, ‘If I were suffering from mental health problems, I wouldn’t want people knowing about it’ continued to decline, from 50% in 2002 to 45% in 2004 and 41% in 2006. Willingness to provide support and interact with people with mental health problems when considering schizophrenia49.

Nevertheless, campaigns targeted at the general population, intended to counter negative stereotypes and attitudes towards people with mental health problems, do not appear to have much effect. There are few rigorous evaluations done and qualitative evidence suggests they may have an effect but these are usually based on cross- sectional data rather than longitudinal data over time50. Anti-stigma campaigns appear to have some but small effect on attitudes, and only if a reduction in social distance translates into a more inclusive approach towards people with mental health problems make the campaign be successful. Improved direct social contact with people with mental health problems has been shown to reduce stigmatizing attitudes and fear of violence in several studies51 52 53 54.

Targeted campaigns might be more effective, e.g. to try and address the attitudes of a certain target group or to have more specific messages raising awareness about the symptoms of specific conditions such as anxiety and depressive disorders. Target professional population groups may include social care professionals, teachers and the police. In England a short term before and after study of the effectiveness of a mental health training intervention for the police suggested that there was an improvement in understanding of mental health issues and better communication between the police and people with mental health problems improved, although there was no change in the view that those with mental health problems were more likely to be violent56.

Interventions might also be targeted at young people. Special programs that approach children and young people have been developed some of them being really effective in making them understand emotions and feelings of those affected by mental disorders. Awareness regarding the frequency of mental disorders and the impact of emotional reactions towards people with mental

health problems are important57 parts of these programs. Evaluation in England suggests that in the short term at least interventions in school settings can improve attitudes towards people with mental health problems58.

Another example is the rigorous before and after evaluated of a multi-faceted community awareness campaign designed to improve mental health literacy and early help seeking amongst young people that was carried out in Australia. The intervention, which included multimedia, a website, and the use of an information telephone service, was evaluated over a 14-month period using a before and an after approach. It had a significant impact on awareness of mental health campaigns, self- identified depression, help for depression sought in the previous year, correct estimate of prevalence of mental health problems, increased awareness of suicide risk, and a reduction in perceived barriers to help seeking. The authors also suggested that the benefits of the campaign may be conservative as a small amount of print material was distributed in the comparison region used in the analysis.

Conclusions

In the European Union poor mental health has an important personal, societal and economic impact. Prejudice, stigma and discrimination associated with poor mental health amplify these impacts. The existing evidence points towards the negative attitudes towards people with mental health problems due to low mental health literacy and inadequate sensationalizing messages promoted in the media. Stigma increases social distance, reduces the likelihood of an individual becoming employed or accessing health care services.

References

1.Global Health Estimates: Deaths, disability-adjusted life year (DALYs), years of life lost (YLL) and years lost due to disability (YLD) by cause, age and sex, 2000–2012. Geneva: World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/, accessed 21 September 2015).

2.Corrigan P: On the Stigma of Mental Illness Washington,D.C., American Psychological Association; 2005.

3.Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC: Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophr Bull 2004, 30:481-491.

4.Wahl OF: Media Madness: Public Images of Mental Illness New Brunswick, New Jersey, Rutgers University Press; 1995.

5.Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC: On describing and seeking to change the experience of stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2002, 6:201-231.

6.http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_ 2004update_part3.pdf?ua=1

7.http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_ 2004update_part3.pdf?ua=1

8.World Health Organization. “Investing in mental health”. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

9.http://www.uniteforsight.org/mental-health/module6

10.Hämäläinen J, Isometsä E, Sihvo S, Kiviruusu O, Pirkola S,general population. Depression and Anxiety 2008, 25:27-37.

11.Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H: Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004, 420(Sppl):47-54.

12. Kessler RC, Berglund PC, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. JAMA 2003, 289:3095-3105.

13.Satcher D: Mental Health: A report of the Surgeon General: Office of the U.S.Surgeon General 1999.

14.Corrigan P: How Stigma Interferes With Mental Health Care. American Psychologist 2004, 7:614-625.

15.http://www.mentalhealth.wa.gov.au/mental_illness_and_health/mh_stigma.aspx

16.World Health Organization. 2003. “Investing in mental health”. Retrieved 7/2/2012.

17.World Health Organization. (2001). The World Health Report 2011. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva: World Health Organization.

18.Crisp A, Gelder MG, Goddard E, Meltzer H: Stigmatization of people with mental illnesses: a follow-up study within the Changing Minds campaign of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. World Psychiatry 2005,4:106-113.

19.Health D: Attitudes to Mental Illness 2003 Report London, Department of Health; 2003.

20.http://www.mentalhealth.wa.gov.au/mental_illness_and_health/mh _stigma.aspx

21.Wright A, McGorry PD, Harris MG, Jorm AF, Pennell K: Development and evaluation of a youth mental health community awareness campaign – The Compass Strategy. BMC Public Health 2006,6:215.

22.Saxena, S., Thornicroft, G., Knapp, M., Whiteford, H. (2007). Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet,370: 878-89.

23.Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY: Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull 2004, 30:511-541.

24.Alonso, J., Buron, A., Bruffaerts, R., He, Y., Posada-Villa, J., Lepine, J-P., Angermeyer, M.C., Levinson, D., Girolamo, G., Tahimori, H., Mneimneh, Z.N., Medina-Mora, M.E., Ormel, J., Scott, K.M., Gureje, O., Haro, J.M., Gluzman, S., Lee, S., Vilagut, G., R.C. Kessler, Von Korff, M. (2008). Association of perceived stigma and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 118: 305-314.

25.Schomerus G., Matschinger H., Angermeyer M. C.:The stigma of psychiatric treatment and help-seeking intentions for depression Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2009) 259:298–306

26.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G et al (2007) Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 6:177

27.Deisenhammer EA, Huber M, Kemmler G, Weiss EM, Hinterhuber H (2007) Suicide victims’ contacts with physicians during the year before death. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 257:480–485

28.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G et al (2007) Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry 6:177

29.Andrews G, Issakidis C, Carter G (2001) Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. Br J Psychiatry 179:417–425

30.Burns T, Eichenberger A, Eich D, Ajdacic-Gross V, Angst J, Rossler W (2003) Which individuals with affective symptoms seek help? Results from the Zurich epidemiological study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 108:419–426

31.Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet EJ, Schulberg HC (1988) Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord 14:223–234

32.Leaf PJ, Livingston MM, Tischler GL, Weissman MM, Holzer CE, Myers JK (1985) Contact with health-professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Med Care 23:1322–1337

33.Huberman AM, Miles MB (1994) Data management and analysis methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications, London, pp 428–444

34.Schomerus G., Matschinger H., Angermeyer M. C.:The stigma of psychiatric treatment and help-seeking intentions for depression Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2009) 259:298–306

35.Andlin-Sobocki, P., et al., Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol, 2005. 12 Suppl 1: p. 1-27.

36.Knapp, M., Hidden costs of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry, 2003. 183: p. 477-8.

37.Thornicroft, G., et al., The personal impact of schizophrenia inEurope. Schizophr Res, 2004. 69(2-3): p. 125-32.

38.van Wijngaarden, B., A.H. Schene, and M.W. Koeter, Family caregiving in depression: impact on caregivers’ daily life, distress, and help seeking. J Affect Disord, 2004. 81(3): p. 211-22.

39.van Wijngaarden, B., A.H. Schene, and M.W. Koeter, Family caregiving in depression: impact on caregivers’ daily life, distress, and help seeking. J Affect Disord, 2004. 81(3): p. 211-22.

40.Anderson, R., R. Wynne, and D. McDaid, Housing and employment, in Mental Health Policy and Practice Across Europe, M. Knapp, et al., Editors. 2007, Open University Press: Buckingham.

41.All Party Parliamentary Group on Prison Health, The mental health problem in UK HM Prisons. 2006, House of Commons: London.

42.Mansell, J., et al., Deinstitutionalisation and community living – outcomes and costs: report of a European Study. Volume 1: Executive Summary. 2007, Tizard Centre, University of Kent: Canterbury. 13

43.Thornicroft, G., et al., The personal impact of schizophrenia in Europe. Schizophr Res, 2004. 69(2-3): p. 125-32.

44.Matschinger, H. and M.C. Angermeyer, The public’s preferences concerning the allocation of financial resources to health care: results from a representative population survey in Germany. Eur Psychiatry, 2004. 19(8): p. 478-82.

45.Schomerus, G., H. Matschinger, and M.C. Angermeyer, Preferences of the public regarding cutbacks in expenditure for patient care: are there indications of discrimination against those with mental disorders? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 2006. 41(5): p. 369-77.

46.TNS, Attitudes to mental illness 2007. 2007, Office of National Statistics: London.

47.Scheff, T., The role of the mentally ill in the dynamics of mental disorder: a research framework. Sociometry, 1963. 26: p. 436-453.

48.Angermeyer, M.C. and B. Schulze, Reinforcing stereotypes: how the focus on forensic cases in news reporting may influence public attitudes towards the mentally ill. Int J Law Psychiatry, 2001. 24(4-5): p. 469-86.

49.Braunholtz, S., et al., Well? What do you think? (2006): The third national Scottish survey of public attitudes to mental health, mental wellbeing and mental health problems. 2007, Scottish Government Social Research: Edinburgh.

50.Crisp, A., L. Cowan, and D. Hart, The College’s Anti-Stigma Campaign, 1998 -2003. A shortened version of the concluding report. Psychiatric Bulletin, 2004. 28(4): p. 133-136.

51.Angermeyer, M.C. and S. Dietrich, Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: a review of population studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 2006. 113(3): p. 163-79.

52.Thornicroft, G., et al., Reducing stigma and discrimination: Candidate interventions. Int J Ment Health Syst, 2008. 2(1): p. 3.

53.Phelan, J.C. and B.G. Link, Fear of people with mental illnesses: the role of personal and impersonal contact and exposure to threat or harm. J Health Soc Behav, 2004. 45(1): p. 68-80.

54.Corrigan, P.W., et al., Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophr Bull, 2001. 27(2): p. 187-95.

55.Lauber, C., Stigma and discrimination against people with mental illness: a critical appraisal. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc, 2008. 17(1): p. 10-3.

56.Pinfold, V., et al., Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination– evaluating an educational intervention with the police force in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 2003. 38(6): p. 337-44.

57.Rose, D., et al., 250 labels used to stigmatize people with mental illness. BMC Health Serv Res, 2007. 7: p. 97.

58.Pinfold, V., et al., Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry, 2003. 182: p. 342-6.

***