CLINICAL STUDY OF THE MENTATION, BEHAVIOR AND MOOD DISORDERS IN PARKINSON’S DISEASE

Abstract

Introduction: Parkinson's disease is a general invalidating neurodegenerative disease. The impaired non-motor functions are well recognized as part of the clinical course of the disease with great impact over the quality of life of the patients. On the other hand, they are highly unrecognized by clinicians and pose great difficulty in detection and measurement. The UPDRS is widely used to assess and follow up PD patients and Part I is used to assess non motor functions such as mentation, behavior and mood disorders. Therefore, we used it in our study for the assessment of the prevalence of the non-motor symptoms measured by UPDRS Part I in PD patients. Objective: To show that there's high prevalence of mentation, behavior and mood disorders as measured by UPDRS Part I in PD patients. Methods: 293 patients with Parkinson's disease (129 men and 164 women) aged 58-79, randomly picked for an 8-year period (2005-2012) were studied. The study used the following assessment tools: І. Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; Modified Hoehn and Yahr scale for assessment of clinical symptoms; Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale. Statistical methods for processing the data received – SPSS statistics software with analysis of variances and alternates was used. Results: The mentation, behavior and mood functions were studied in 293 patients diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. Lack of motivation/initiative was most frequently observed – in 245 patients (83.6%), followed by depression – in 200 patients (68.2%)and memory disorders – in 199 patients (67.9%). Thought disorder was the least frequent (26.9%). As a result of these disorders all patients had a considerably reduced quality of life mainly due to the development of significant cognitive impairment. Conclusion: This results confirm the observation that mentation, behavior and mood dysfunctions are a highly prevalent and important feature of PD. Therefore, treating physicians should look for them routinely. The UPDRS showed that it is sensitive and reliable tool for detecting such symptomatology

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex neurodegenerative condition manifested by characteristic motor impairment and a wide array of non-motor symptoms (NMS) (1, 2). Recently, sleep, fatigue, mood, cognition, pain and autonomic disorders have been recognized as important components of the disease, with a consistent impact on patients’ health and quality of life (3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Despite of these problems and the high burden of NMS in most patients (4, 8) NMS remain frequently neglected (9) or undocumented (10). NMS thus present one of the biggest challenges for management by the clinician and a comprehensive assessment that includes NMS as well as motor state of the patient is essential (11). NMS can be assessed by several tools specifically designed for these s y m p t o m s , i n c l u d i n g t h e N M S q u e s t i o n n a i r e ( N M S Q u e s t ) ( 1 2 ) , t h e u n i f i e d P D r a t i n g s c a l e (UPDRS)(13) and the PD sleep scale (PDSS) (14). Pathophysiological, NMS may be related to both dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic alterations. For example, PET studies reported dopamine dysfunction at the hypothalamus (15). Degeneration of cholinergic adrenergic or serotoninergic pathways could also contribute to NMS genesis (16). Moreover, NMS can precede motor symptoms and thus PD diagnosis (17). Some studies suggest that NMS are common in all stages of PD and more common as the motor symptoms progression regardless of age of onset, levodopa dosage or disease duration. The most prevalent NMS in this study were highly similar to other previous international studies using the 30-item NMSQuest (18, 19 and 20). Non-motor symptoms dominate the clinical picture as PD progresses and may also contribute to shortened life expectancy (2,21). Most do not respond to, and may be exacerbated by, dopamine replacement therapy (22). NMSs also account for the burden of hidden costs such as sick leave, early retirement and informal care not only for patients but also for caregivers in certain instances. The cost burden of NMSs is significantly high, especially in patients with advanced PD and increasingly severe symptoms, for which there is a poorer quality of life, reduced productivity and a greater need for health-care services, which in turn have an impact on direct and indirect costs. Thus, identifying disease-modifying treatments early in the disease, before any functional or motor disability appears, is critical in reducing costs and preserving quality of life. Evidence suggests that initial therapy with non- levodopa agents is cost-effective, prolongs time to levodopa initiation and delays the onset of dyskinesia (23).

There is a significant interrelationship of severity of disease, quality of life, patients and caregiver’s burden, and cost of illness. NMSs contribute to the overall PD burden, which is a major determinant of quality of life. An increasing awareness of ‘at-risk’ individuals, based on detection of some or a combination of NMSs, is essential for an early identification of PD patients. Identification of prodromal patients plays a key factor in preventing the burden of economic costs and improving quality of life of patients and caregivers. Keeping this in mind, it becomes important to optimize the management of all aspects of NMSs in PD (24). Therefore we conducted our study to evaluate the high prevalence of non-motor symptoms in PD patients, particularly those measured by UPDRS Part I as it is one of the most used clinical scales in PD and thus with great clinical significance.

OBJECTIVE

To show the high prevalence of mentation, behavior and mood disorders as measured by UPDRS Part I in PD patients.

MATERIALAND METHOD

293 out patients with PD (129 men and 164 women) aged 58-79, all retired due to illness (PD), randomly selected in terms of different PD stages for an 8-year period (2005- 2012) were investigated after the inform consent was signed. They were outpatient recruited from a PD center of Department of Neurology and Psychiatry. The patients received L-DOPA, dopamine agonists and antioxidants. The same team member who performed the clinical diagnosis also applied the scale. The patients have not been researched for concomitant illnesses. The study used the following assessment tools:

І. Unified Parkinson’s disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) – Part I: evaluation of mentation, behavior, and mood. UPDRS is the most used scale to follow the longitudinal course of PD. (16, 17)

ІІ. Modified Hoehn and Yahr scale for assessment of clinical symptoms;

ІІІ. Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale; Modified Hoehn and Yahr scale for assessment of clinical symptoms and Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale are parts of UPDRS, but are mentioned separately because were used alone in the process of diagnosing the disease. The complete UPDRS was used latter for the measurement of the progression of the disease.

IV. Statistical methods for processing the data received –SPSS 11 software with analysis of variances and alternates was used.

RESULTS

MENTATION, BEHAVIOR AND MOOD.

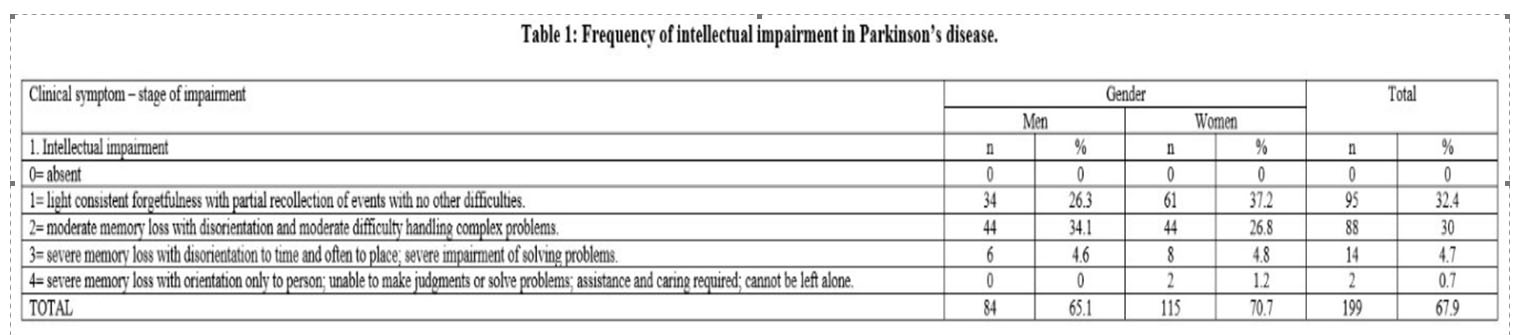

1. Intellectual Impairment. That symptom was observed in 199 patients (67.9%). No significant gender-related differences were found. From Part 1 of UPDRS the item 1 – “light consistent forgetfulness with partial recollection of events” and the item 2 – “moderate memory loss with disorientation to time and often to place” were considerably prevalent as compared to the item 4 “severe memory loss with orientation only to person” (p<0.05%) (Table 1).

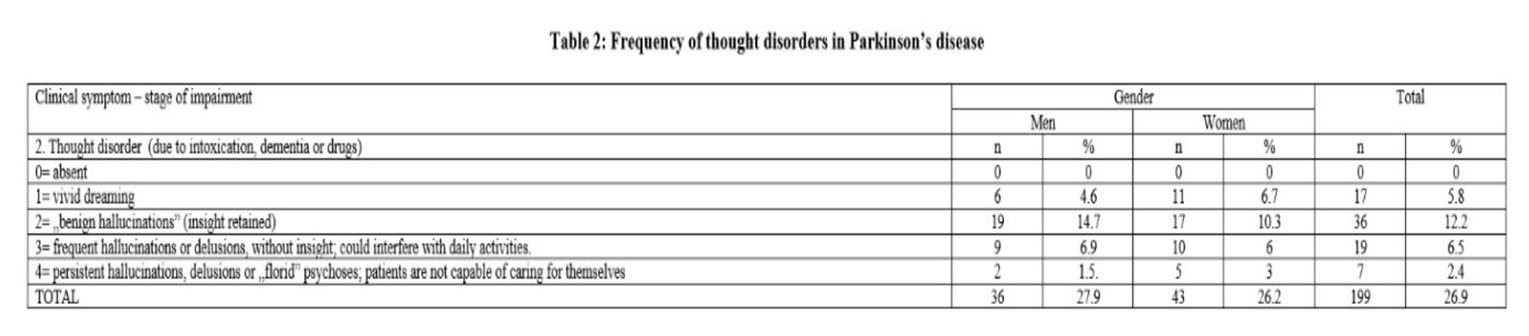

2. Thought disorder. Thought disorder was found in 79 patients (26.9%). The item 2 – “benign hallucinations “with retained insight was most frequently observed. The item 3 – “Frequent hallucinations or delusions were almost equally frequent. Then came the item 1 – “vivid dreaming”, while persistent hallucinations and delusions were the least frequent. No significant gender-related differences were found (Table 2).

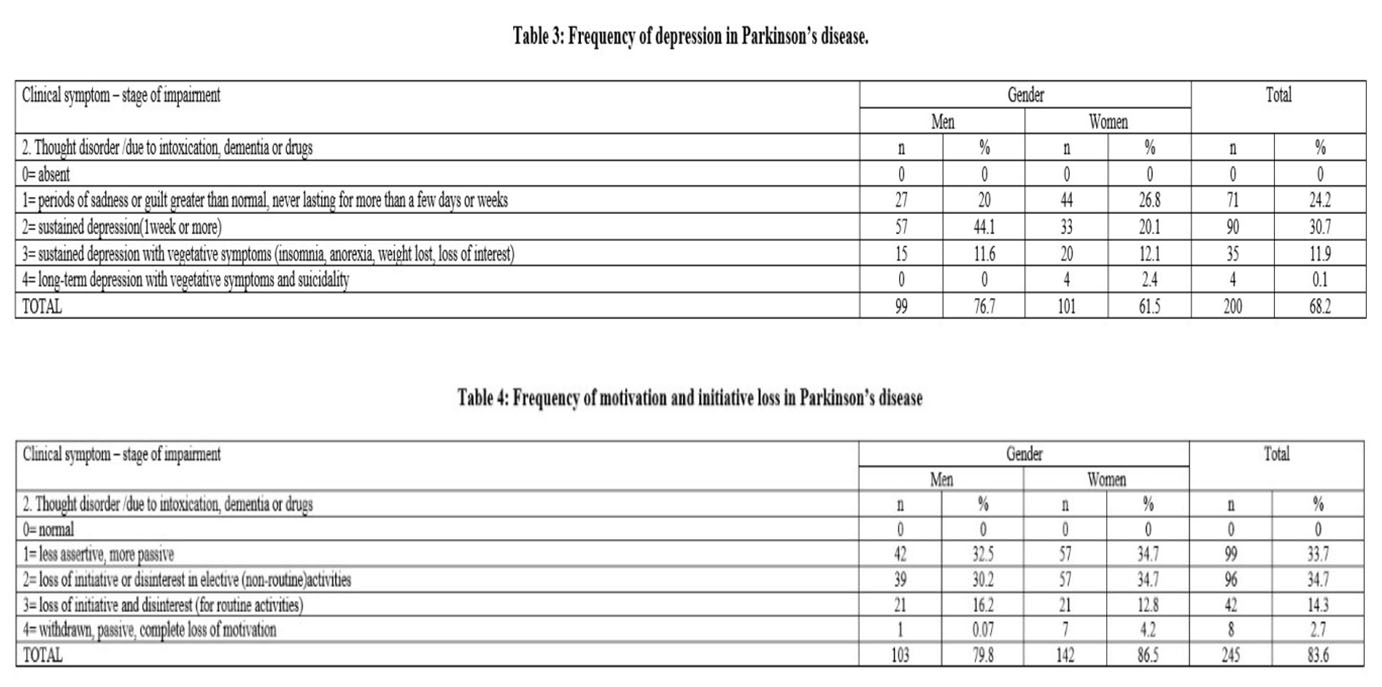

3. Depression (depression symptoms) the item 2 – “sustained depression, lasting more than a week was the most frequently observed in both genders. It was found in 90 patients (30.7%), followed by the item 1 – “periods of sadness and guilt”. Their values increased significantly as compared to the item “long-term depression with vegetative symptoms and suicidal thoughts or intentions” (p<0.05%) (Table 3).

4. Motivation/Initiative. Lack of motivation and loss of initiative were most frequent among the PD patients. Those symptoms were found in 245 patients (83.6%). They were less assertive and more passive. Complete loss of motivation was the least frequent, the low results being statistically significant as compared to the milder impairment stages (p<0.01%) (Table 4). Apathy was observed in 54% of the patients diagnosed with mild to moderate PD related depressive symptoms

CONCLUSIONS:

This study showed moderate to high prevalence of non- motor neuropsychiatric disturbances in patients with PD in different stages of the disease as measured by the UPDRS Part I. This confirms that they are important part of the disease. Therefore, treating physicians should look for them routinely in their effort for the improvement of quality of life in patients with PD. The UPDRS showed that it is sensitive and reliable tool for detecting such symptomatology.

DISCUSSIONS:

As PD is a multidimensional disorder, the disease progression and treatment efficacy should be assessed not only through motor symptoms but also through psychopathological and autonomic symptoms. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) was developed as a brief, valid, and reliable scale for the assessment of activities and non-motor symptoms in PD and has replaced many of the older assessment scales. (25,

26) Cognitive disorders in PD consist first of an intellectual slowing and difficulties to organize and manage the intellectual capacities, with preservation of global cognitive efficiency for long time.(27) Eventually, these disturbances can increase with the time and even progress to dementia. It is important to distinguish mild cognitive impairment from dementia, the latter being present only in a moderate percentage of PD patients. Our results revealed high prevalence of intellectual impairment (67.9%) as measured by the UPDRS which underlines the significance of its early recognition. Hallucinations occur usually in a normal state of consciousness, without delirium, and have a chronic course. (28) The prevalence of complex visual hallucinations ranges from 22 to 38%.(29) Risk factors for hallucinations are older age, long duration of the disease, cognitive impairment, severity of PD symptoms, sleep disorders (somnolence), and visual disorders. (30) Risk of psychotic symptoms is increased in late onset PD, in patients taking high doses of dopaminergic drugs and suffering of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). Hallucinations must be identified by systematically questioning the patient.

Visual hallucinations are surprising, but their intensity is quite variable. Benign hallucinations are limited to presence sensation, passing lights or visions at periphery of the visual field, with great tolerance by the patient. (31) Our results showed moderate frequency of thought disorder in our study population. Thought disorder was found in 79 patients (26.9%) and the item “benign hallucinations “with retained insight was most frequently observed.

Depression occurs at any stage of the disease, even at the beginning or sometimes many years before the onset of the disease. (32) Depression can occur in up to 27.6% of PD patients during early stages of the disease.(33) Depression may consist in major depressive disorder (17%), minor depressive disorder (22%), and dysthymia (13%), and clinical significant depressive symptoms are present in 35% of PD patients. (34, 35) Our results show that the item “sustained depression, lasting more than a week” was the most frequently observed in both genders. It was found in 90 patients (30.7%) in our study sample.

Apathy consists in a loss of motivation, which appears in emotional, intellectual domains and in the behavior. For the diagnosis of apathy, the decrease of spontaneous acting must not be imputable to motor disability, nor to severe cognitive decline. (36, 37) Indeed, this neuropsychiatric symptom is frequent, with a prevalence of 30% to 40% in PD patients. (38, 39) Apathy is one of the major determinants of a reduced quality of life in PD, (40) even at early stages. As such, early diagnosis and efficient therapy are important in order to avoid further consequences on quality of life and disability. Lack of motivation and loss of initiative were most frequent among the PD patients. Those symptoms were with high prevalence in our study sample and was found in 245 patients (83.6%).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

All the authors had an equal contribution and have similar rights. All the authors approved the final version of this article.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no conflict of interest for this article.

LIST OFABBREVIATIONS:

PD – Parkinson’s disease

UPDRS – Unified Parkinson’s disease Rating Scale

MMSE – –MiniMental State Examination МОСА – Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale MCI – Mild Cognitive Impairment

NMS – Non-motor symptoms

REFERENCES

1.Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T, et al. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2009;

373:2055–2066.

2.Chaudhuri KR, Healy D, Schapira AH et al. The non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Diagnosis and Management. Lancet Neurol

2006; 5:235–245.

3.Rahman S, Griffin HJ, Quinn NP et al. Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: the relative importance of the symptoms. Mov Disord 2008;

23:1428–1434.

4.Barone P, Antonini A, Colosimo C et al. The PRI-AMO study: a multicenter assessment of nonmotor symptoms and their impact on quality of life in Parkin-son’s disease. Mov Disord 2009; 24:1641–1649.

5.Qin Z, Zhang L, and Sun F et al. Health related quality of life in early Parkinson’s disease: impact of motor and non-motor symptoms, results from Chinese levodopa exposed cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord

2009; 15: 767–771.

6.Li H, Zhang M, Chen L et al. Nonmotor symptoms are independently associated with impaired health-related quality of life in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2010; 25:2740–2746.

7.Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtis MM et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s dis-ease. Mov Disord 2011; 26:399–406.

8.Martinez-Martin P, Schapira AH, and Stocchi F et al. Prevalence of nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease in an international setting: study using nonmotor symptoms questionnaire in 545 patients. Mov Disord 2007; 22:1623–1629.

9. Shulman LM, Taback RL, Rabinstein AA et al. Non recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2002; 8:193–197.

10.Chaudhuri KR, Prieto-Jurcynska C, Naidu Y et al. The nondeclaration of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease to health care professionals: an international study using the nonmotor symptoms questionnaire. Mov Disord 2010; 25:697–701.

11.Chaudhuri KR, Yates L, Martinez-Martin P. The non-motor symptom complex of Parkinson’s disease: a comprehensive assessment is essential. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2005; 5:275–283.

12.Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P. Quantitation of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease. Eur J. Neurol 2008;15(2):2-7

13.Fahn S, Elton RL and members of the UPDRS Developping commitee, “Unified Parkinson’s Disease rating scale”. In: Fahn S, Mardsen CD, Goldstein M (eds). Recent developments in Parkinson’s Disease. New York: McMillan, 1987, 153-163

14.Chaudhuri KR, Pal S, DiMarco A et al. The Parkinson’s disease sleep scale: a new instrument for assesing sleep and nocturnal disability in Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73 (6): 629- 635

15.Chaudhuri KR. The dopaminergic basis of sleep dysfunction and nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: evidence from functional imaging. Exp Neurol 2009; 216 (2): 247-248

16.Barone P. Neurotransmission in Parkinson’s disease: beyond dopamine. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17 (3): 364-376

17.Chaudhuri KR, Schapira AH. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8(5): 464-474

18. Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Schapira AH et al. International multicenter pilot study of the first comprehensive self-completed non- motor symptoms

Questionnaire for Parkinson’s disease: the NMSQuest study. Mov Disord 2006; 21:916-23.

19. Crosiers D, Pickut B, Theuns J et al. Non-motor Symptoms in a Flanders-Belgian population of 215 Parkinson’s disease patients as assessed by the NonMotor Symptoms Questionnaire. Am J Neurodegener Dis 2012; 1:160-7

20. Gan J, Zhou M, Chen W, Liu Z. Non-motor symptoms in Chinese Parkinson’s disease patients. J Clin Neurosci 2014; 21(5):751-4

21. Poewe W. The natural history of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 2006; 253:VII2-VII6.

22. Haycox A, Armand C, Murteira S et al. Cost effectiveness of rasagiline and ramipexole as treatment strategies in early Parkinson’s disease in the UK setting: An economic Markov model evaluation. Drugs Aging 2009; 26:791-801.

23. Chaudhuri KR, Martinez-Martin P, Antonini A. 2011; HIII (97): 15. ISBN 978-1-907673-23-8.

24. Treves TA, Chandra V, Korczyn AD. Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases: epidemiological comparison. Descriptive aspects.

Neuroepidemiology 1993; 12:336–344.

25. Fran S, Elton RL, members of the UPDRS Developing Committee Unified Disease Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. In: Fran S, Marsden CD, Calne DB et al. (eds). Recent Developments in Parkinson’s disease. Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Healthcare Information, 1987, 153-163.

32. Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson’s disease. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Movement Disord 2003; 18:738–50.

33. Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Abe K et al. International study on the psychometric attributes of the Non-Motor Symptoms Scale in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2009; 73(19): 1584–1591.

34. Dubois B, Pillon B. Cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 1997; 244(1): 2–8.

35. Fénelon G, Mahieux F, Huon R et al. Hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. Prevalence, phenomenology and risk factors. Brain J 2000; 123:733–745.

36. Fenelon G and Alves G. Epidemiology of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. J Neur Sci 2010; 289:12–17.

37. Diederich NJ, Goetz CG, Pappert EJ et al. Poor visual discrimination and visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease.

Clin Neuropharmacol 1998; 21:289–295.

38. Tom T, Cummings JL. Depression in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacological characteristics and treatment. Drugs and Aging 1998; 12(1): 55–74.

39. Ravina B, Camicioli R, Como PG et al. The impact of depressive symptoms in early Parkinson disease. Neurology 2007; 69(4): 342–347.

40. Reijnders JSAM, Ehrt U, Weber WEJ, Aarsland D, Leentjens AFG. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2008; 23(2): 183–189.

41. Tan LCS. Mood disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat D 2012; 18(1): 74–76.

42. Marin RS. Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsych Clin N 1991; 3(3): 243–254.

43. Starkstein SE, Leentjens AFG. The nosological position of apathy in clinical practice,” J Neurol Neurosur Ps 2008; 79(10) 1088–1092.

44. Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Preziosi TJ, Andrezejewski P, Leiguarda R, Robinson RG. Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsych Clin N 1992; 4(2): 134–139.

45. Sockeel P, Dujardin K, Devos D, Denève C, Destée A, Defebvre L. The Lille apathy rating scale (LARS), a new instrument for detecting and quantifying apathy: validation in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosur Ps 2006; 77(5) 579–584.

46. Benito-León J, Cubo E, Coronell C. Impact of apathy on health- related quality of life in recently diagnosed Parkinson’s disease: the ANIMO study. Movement Disord 2012; 27(2):211–218.

***